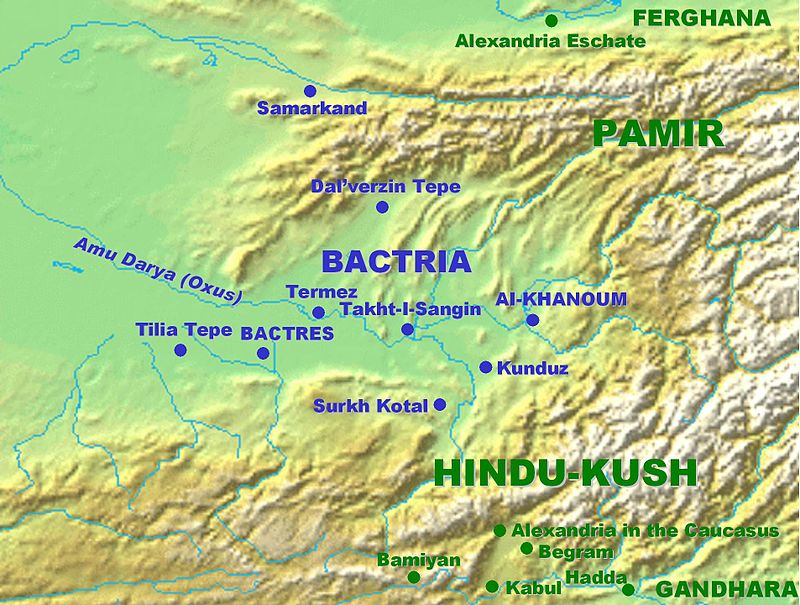

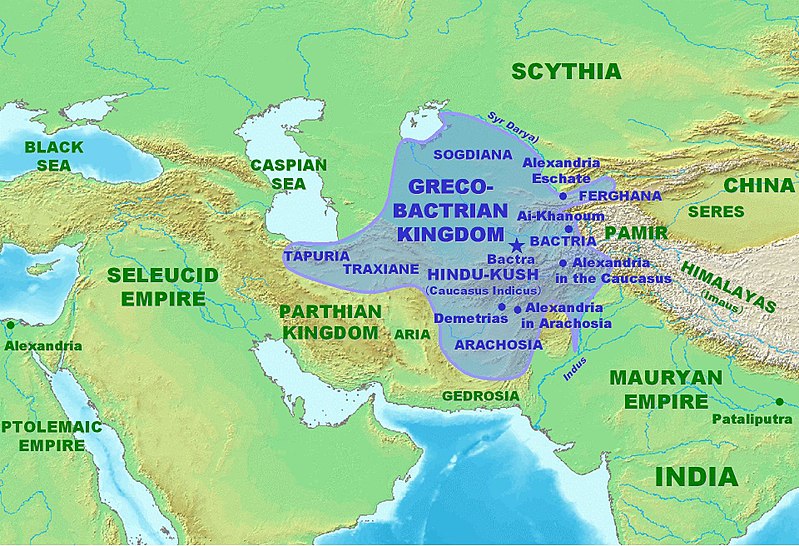

Η Βακτριανή είναι ο χώρος του σημερινού βόρειου Αφγανιστάν και των προς αυτό συνοριακών περιοχών του Τουρκμενιστάν, του Ουζμπεκιστάν και του Τατζικιστάν. Η Βακτριανή είναι μια μεγάλη κοιλάδα που περικλείεται από τα Παμίρ στα βόρεια και στα ανατολικά και από τον Ινδοκαύκασο (Χιντού Κους) στα νότια. Στα δυτικά η κοιλάδα εκτείνεται μέχρι την Σογδιανή που βρίσκεται στα βόρεια και βορειοδυτικά της Βακτριανής και είναι πολύ πιο πεδινή χώρα. Πρωτεύουσα της Βακτριανής ήταν τα Βάκτρα (σήμερα Μπαλχ) που αποτελούσαν πολύ σημαντικό κέντρο πολιτισμού πάνω στους Ιστορικούς Δρόμους του Μεταξιού στα προϊσλαμικά και στα ισλαμικά χρόνια. Δυστυχώς σχεδόν τα πάντα από τα αρχαία, προϊσλαμικά, Βάκτρα έχουν χαθεί, διότι θα έπρεπε να εκκενωθεί η πόλη Μπαλχ για να γίνουν εκτεταμένες ανασκαφές, αν και βέβαια το περίφημο κάστρο του Μπαλχ σαφέστατα και αντιστοιχεί στην αρχαία, προϊσλαμική ακρόπολη των Βάκτρων.

Οι σήμερα σωζόμενοι, ανεσκαμμένοι και μελετημένοι χώροι του επίκεντρου της Αρχαίας Βακτριανής είναι: το Τίλια Τεπέ (Tilia Tepe), όπου ο Ρωσσο-Ποντιος Βίκτωρ Σαριγιαννίδης έφερε στο φως τα πιο εντυπωσιακά βακτριανικά μνημεία και απίστευτο αριθμό χρυσών αντικειμένων, το Τερμέζ (Termez), το Σουρχ Κοτάλ (Surkh Kotal), το Κουντούζ (Kunduz), το Ταχτ-ι Σανγκίν (Takht-i Sangin), το Νταλβερζίν Τεπέ (Dalverzin Tepe), και το Άι Χανούμ (Ai Khanoum). Βεβαίως η Βακτριανή εξικνείται και πιο νότια μέχρι την Αλεξάνδρεια του Καυκάσου (η μεταγενέστερη Καπίτσα, πρωτεύουσα της Αυτοκρατορίας του Κουσάν) και το Μπαγκράμ (Begram), στις νότιες υπώρειες του Ινδοκαύκασου λίγο βορειώτερα της Καμπούλ. Αλλά η Βακτριανή δεν φθάνει τόσο βόρεια όσο η Αλεξανδρεια Εσχάτη στην Κοιλάδα της Φεργάνα, βορείως των Παμίρ: εκείνη η περιοχή είναι τμήμα της Σογδιανής.

Σχετικά:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Termez

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Surkh_Kotal

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kunduz

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Takhti-Sangin

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dalverzin_Tepe

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Begram_ivories

https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Begram

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alexandria_in_the_Caucasus

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alexandria_Eschate

Κεντρικό γεωγραφικό χαρακτηριστικό της Βακτριανής είναι το γεγονός ότι η χώρα διασχίζεται από τον Ώξο (αρχαία ιρανικά: Γιάχσα), ένα μεγάλο ποτάμι που σήμερα ονομάζεται Αμού Ντάρυα κι εκβάλλει στην Αράλη, όπου επίσης εκβάλλει, ρέοντας πολύ πιο ανατολικά, και ο Ιαξάρτης (αρχαία ιρανικά: Γιάχσα Άρτα: ‘Άνω Ώξος’), ο οποίος σήμερα λέγεται Συρ Ντάρυα. Ο Ώξος (Αμού Ντάρυα) σχηματίζεται από την συμβολή πολλών παραποτάμων που σχηματίζονται στα βουνά που περιβάλλουν την Βακτριανή από τα βόρεια, τα ανατολικά και τα νότια: ο Παντζ και ο Κόκτσα είναι δύο από αυτούς τους παραποτάμους.

Σχετικά:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Amu_Darya

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Syr_Darya

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Panj_River

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kokcha_River

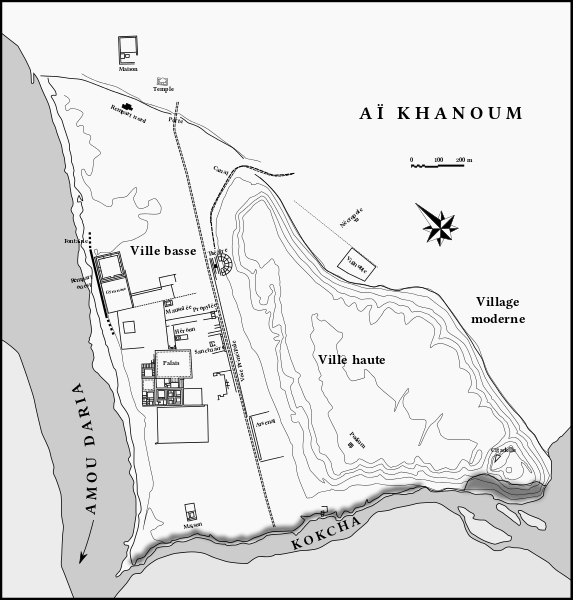

Η Άι Χανούμ (Ἀλεξάνδρεια ἡ ἐπὶ τοῦ Ώξου) έχει ανεγερθεί στην συμβολή αυτών των δύο παραποτάμων του Ώξου, του Παντζ και του Κόκτσα. Επειδή ο Παντζ είναι ήδη πολύ μεγαλύτερος του Κόκτσα, οι Αρχαίοι Έλληνες που θεμελίωσαν εδώ μια πόλη εξέλαβαν τον Παντζ ως τον αρχικό ρου του Ώξου. Το νεώτερο, ουζμπεκικό όνομα της περιοχής και του κοντινού χωριού σημαίνει ‘η Κυρία Σελήνη’ και αναφέρεται σε μια ντόπια γυναίκα της οποίας το όνομα ήταν Άι (‘σελήνη’). Αντίθετα με τις αραβικές λέξεις για την σελήνη που μπορούν να είναι ονόματα ανδρών (όπως π.χ. Μπαντραντίν: ‘φεγγάρι της θρησκείας’), στις τουρανικές (Turkic) γλώσσες η λέξη ‘σελήνη’ είναι όνομα γυναικών. Το σημείο βρίσκεται πολύ κοντά στην μεθόριο του Τατζικιστάν.

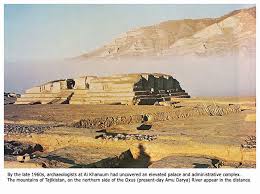

Η Άι Χανούμ ως χώρος αρχαιοτήτων ανακαλύφθηκε μόλις στην δεκαετία του 1960 από τον Χαν Γολάμ Σερβάρ Νασέρ, ο οποίος εξαιτίας των ευρημάτων που εντοπίστηκαν εκεί κάλεσε τον Αμερικανό αρχαιολόγο Daniel Schlumbergerτου οποίου ομάδα γρήγορα ταύτισε τον χώρο με την μέχρι τότε γνωστή μόνον χάρη σε ιστορικές πηγές Αλεξάνδρεια επί του Ώξου. Οι πιο συστηματικές ωστόσο ανασκαφές έγιναν από τον Γάλλο αρχαιολόγο Paul Bernard της Γαλλικής Αρχαιολογικής Αντιπροσωπείας στο Αφγανιστάν (DAFA: Délégation archéologique française en Afghanistan) από το 1964 μέχρι το 1978.

Σχετικά:

https://af.ambafrance.org/-Delegation-archeologique-francaise,226-

https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/D%C3%A9l%C3%A9gation_arch%C3%A9ologique_fran%C3%A7aise_en_Afghanistan

Το 1978 οι ανασκαφές διακόπηκαν λόγω της σοβιετικής εισβολής και μάλιστα στο συγκεκριμένο σημείο έγιναν συγκρούσεις επειδή οι γαλλικές μυστικές υπηρεσίες (δηλαδή οι ίδιοι οι αρχαιολόγοι κι οριενταλιστές της ομάδας του DAFA), περιμένοντας την σοβιετική εισβολή, είχαν ήδη οργανώσει ένοπλες ομάδες Τατζίκων του Αφγανιστάν για να αντιμετωπίσουν τους Σοβιετικούς ή να οργανώσουν σχετική αντίσταση μετά την κατάληψη. Αυτοί οι πρώτοι αντιστασιακοί κατά των Σοβιετικών, πρέπει να τονιστεί, ήταν μουσουλμάνοι αλλά δεν ήταν ισλαμιστές, δεν είχαν επαφή με την Σαουδική Αραβία, κι απλώς δεν ήθελαν να γίνουν τμήμα της ΕΣΣΔ. Μετά από πολλές δεκαετίες, ο David Adams το 2013 γύρισε ένα ντοκυμαντέρ σχετικά με τις αρχαιότητες που είχαν ανασκαφεί στην Άι Χανούμ με τίτλο Alexander’s Lost World.

Είναι πιθανόν η Αλεξάνδρεια επί του Ώξου να ταυτίζεται με την γνωστή απο ποικίλες ιστορικές πηγές Ευκρατίδεια, ή αλλοιώς και Ευκρατιδία ( اروکرتیه – Arukratiya – Eucratidia), την οποία ανήγειρε (ή επεξέτεινε) ο Ευκρατίδης Α’ ο Μέγας (170-145 π.Χ.). Δεν υπάρχει ακόμη συμφωνία ειδικών αν η πόλη ανεγέρθηκε στα τέλη του 4ου προχριστιανικού αιώνα από τον Αντίοχο Σωτήρα Α’, ή στις αρχές του 3ου προχριστιανικού αιώνα, ή ακόμη κατά τον 2ο προχριστιανικό αιώνα. Πάντως το πιθανώτερο είναι η πόλη να θεμελιώθηκε τον 3ο προχριστιανικό αιώνα και να καταστράφηκε στις νομαδικές επιδρομές του 145 π.Χ.

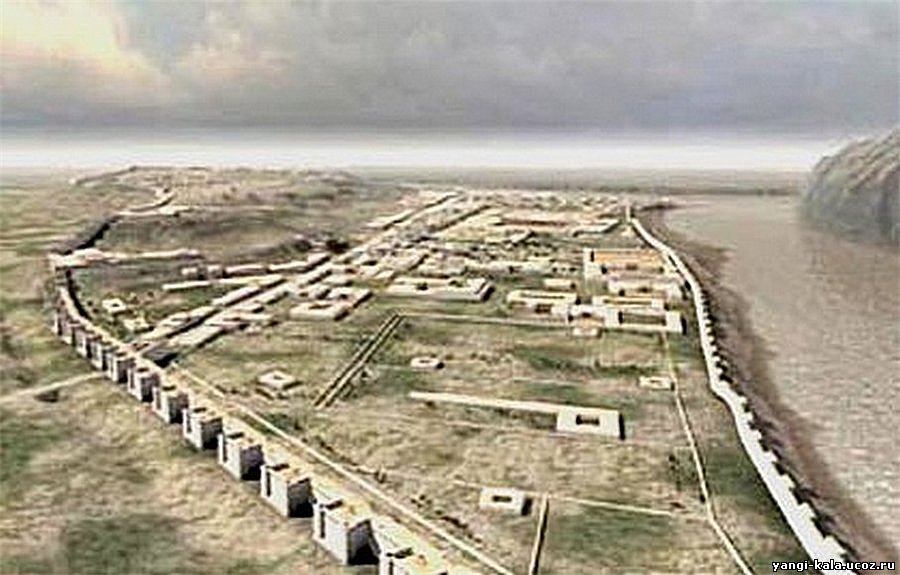

Η μεγάλη πολιτεία (1.5 τχ) με θέατρο, γυμνάσιο, ανάκτορο και κτήρια ελληνικής αρχιτεκτονικής τεχνοτροπίας είχε πολλά κεντρασιατικά, βακτριανικά, χαρακτηριστικά – δείγμα ότι οι κάτοικοι ήταν ανάμεικτοι Έλληνες και Βακτριανοί.

Υπήρχαν μεγάλα τείχη μήκους σχεδόν 4 χμ, ακρόπολη με πύργους, και διάφοροι ναοί όπου ένας βακτριανο-ελληνικός συγκρητισμός σημειώνεται στην αρχιτεκτονική δομή και στην διακόσμηση. Πολλά αγάλματα, ανάγλυφα κι αρχαιοελληνικές επιγραφές έχουν ανασκαφεί και κάποιες επιγραφές αποτελούν δελφικά παραγγέλματα (https://el.wikipedia.org/wiki/Δελφικά_παραγγέλματα).

Για παράδειγμα:

παῖς ὢν κόσμιος γίνου,

ἡβῶν ἐγκρατής,

μέσος δίκαιος,

πρεσβύτης εὔβουλος,

τελευτῶν ἄλυπος.

Δείτε το βίντεο:

Ай Ханум – Александрия Оксианская: древний город Греко-Бактрийского царства в северном афганистане

https://ok.ru/video/1580008868461

Περισσότερα:

Ай-Ханум (перс. آیخانم, узб. Oyxonim), Александрия Оксианская (др.-греч. Ἀλεξάνδρεια ἡ ἐπὶ τοῦ Ὄξου) — древний город Греко-Бактрийского царства, руины которого располагаются в районе Дашти-Кала[en] афганской провинции Тахар, близ границы с Таджикистаном, на левом берегу реки Пяндж у устья реки Кокча. Городище является уникальным памятником эллинистической культуры в Центральной Азии.

Уже в эпоху бронзового века на территории города существовало поселение. Во время походов Александра Македонского, вероятно, здесь предполагалось основать крупный город, форпост восточной Бактрии. Однако реальное заселение датируется временем Селевка Никатора и относится к рубежу IV—III вв. до н. э. Расцвет города приходится на III—II вв. до н. э., когда были возведено большинство зданий. Разрушение города связывается с нашествием индоевропейских кочевых племен (вначале скифов-саков, затем тохаров, или юэчжи) на Бактрию в середине II в. (около 135 г. до н. э.). С тех пор город больше не восстанавливался.

Открытие и исследование города связано с именем афганского короля Захир-Шаха, большого любителя древностей. Во время одного из путешествий короля по регионам страны представители местной администрации устроили для короля традиционную охоту на тигра, но зная о исторических увлечениях Захир-шаха, обставили её так, чтобы маршрут лова проходил по территории, «…где из земли торчали каменные столбы». Король, естественно, обнаружил остатки древних строений и сообщил об этом Даниэлю Шлюмберже, занимавшему тогда пост директора Французской археологической миссии в Афганистане.

Шлюмберже со своим помощником Полем Бернаром выехали на место. Уже сам осмотр территории городища и характер подъёмного материала позволил говорить о уникальном открытии эллинистического города в глубинах Азии (1964 г.). Это открытие существенно изменило представления о характере и качественных характеристиках эллинистической культуры в Азии.

Ещё с XVIII в. европейским учёным были известны монеты высокого качества с удивительно искусно выполненными портретами греческих царей Бактрии. Однако зримых памятников бактрийской культуры, подобных Риму, афинскому Акрополю, или персидскому Персеполю обнаружено не было. Поэтому исследователи оперировали в основном материалами последующих эпох, реконструируя на их основе античную культуру Центральной Азии. Несмотря на огромное количество материалов кушанской эпохи, говорящих о устойчивой античной основе, отсутствие непосредственно эллинистических памятников (за исключением монет) представлялось досадным недоразумением. Особенно остро вопрос об эллинистической культуре Бактрии встал после неудачи с зондажами в Балхе, где эллинистические слои были либо частично скрыты из-за высоко уровня грунтовых вод, или же давали невыразительный материал, что побудило выдвинуть тезис о «бактрийском мираже» (Фуше в 1925 г.), говорящим о том, что Бактрия была слаборазвитой страной, монетные формы для которой делали приезжие греческие мастера, а античные мотивы в буддийские памятниках объяснялись римским (!) влиянием. Более трезво мыслящие исследователи, среди которых особенно выделялся Д. Шлюмберже, предполагали, что отсутствие эллинистических памятников связано с плохой изученностью региона.

Однако ситуация усугублялась общей слабой изученностью эллинистических памятников Востока, что давало повод говорить о слабости греко-македонской колонизации и периферийном значении восточного региона в системе всей античной культуры. Но, как впоследствии оказалось, слабая изученность эллинистической культуры Востока была связана именно с греко-македонской колонизацией, так как большинство современных городов этого региона возникло именно в ту эпоху. Ай-Ханум был единственным крупным эллинистическим городом в Центральной Азии, сохранившимся в таком хорошем состоянии и давшим эталонные памятники эллинистической культуры мирового уровня.

https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ай-Ханум

Δείτε το βίντεο:

Ай Ханум – Александрия Оксианская: древний город Греко-Бактрийского царства в северном афганистане

https://vk.com/video434648441_456240368

Περισσότερα:

Ай-Ханум (перс. آیخانم, узб. Oyxonim), Александрия Оксианская (др.-греч. Ἀλεξάνδρεια ἡ ἐπὶ τοῦ Ὄξου) — древний город Греко-Бактрийского царства, руины которого располагаются в районе Дашти-Кала[en] афганской провинции Тахар, близ границы с Таджикистаном, на левом берегу реки Пяндж у устья реки Кокча. Городище является уникальным памятником эллинистической культуры в Центральной Азии.

Структура греко-бактрийского города была продиктована геологическим строением материкового останца, состоящего из нескольких террас, в соответствии с которыми город делится на три части: Нижний город, на территории которого сосредоточены основные исследованные объекты:

Дворцовый комплекс

Гимнасий

Жилые дома

Героон Кинея (предположительно основателя города)

Храм-мавзолей

Арсенал

Главный храм — сооружение в вавилонском стиле с греческой статуей Зевса внутри

Театр — единственное сооружение подобного рода, открытое в Средней Азии

Акрополь — верхний город, научно практически не исследовался

Цитадель — небольшое укрепление в южном углу акрополя

На развалинах монументального здания эллинистического периода был построен обжигательный горн, когда город Ай-Ханум практически не существовал.

https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ай-Ханум

Δείτε το βίντεο:

Ai Khanoum – Alexandria on the Oxus: City of the Greek Kingdom of Bactria (Northern Afghanistan)

https://orientalgreeks.livejournal.com/1447.html

Δείτε το βίντεο:

Άι Χανούμ – Αλεξάνδρεια επί του Ώξου: Ελληνική Πόλη των Επιγόνων στην Βακτριανή (Βόρειο Αφγανιστάν)

Περισσότερα:

Curtius 7.10.15: Κουίντος Κούρτιος Ρούφος, Historia Alexandri Magni regis Macedonum, βιβλίο έβδομο, κεφ. 10

«…Superatis deinde amnibus Ocho et Oxo, ad urbem Margianam pervenit. Circa eam VI oppidis condendis electa sedes est. Duo ad meridiem versa, IIII spectantia orientem;…»

(μετάφραση:«…Τότε πέρασε τους ποταμούς Ώξο και Ώχο και έφτασε στην πόλη της Μαργιάνα. Γύρω της ίδρυσε έξη πόλεις, δύο νότια και τέσσεριες ανατολικά…»)

Ai-Khanoum (Aï Khānum, also Ay Khanum, lit. “Lady Moon” in Uzbek), possibly the historical Alexandria on the Oxus (Greek: Ἀλεξάνδρεια ἡ ἐπὶ τοῦ Ώξου), possibly later named Eucratidia, Εὐκρατίδεια) was one of the primary cities of the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom from circa 280 BCE, and of the Indo-Greek kings when they ruled both in Bactria and northwestern India, from the time of Demetrius I (200-190 BCE) to the time of Eucratides (170–145 BCE). Previous scholars have argued that Ai Khanoum was founded in the late 4th century BC, following the conquests of Alexander the Great. Recent analysis now strongly suggests that the city was founded c. 280 BC by the Seleucid emperor, Antiochus I Soter. The city is located in Takhar Province, northern Afghanistan, at the confluence of the Panj River and the Kokcha River, both tributaries of the Amu Darya, historically known as the Oxus, and at the doorstep of the Indian subcontinent. Ai-Khanoum was one of the focal points of Hellenism in the East for nearly two centuries until its annihilation by nomadic invaders around 145 BCE about the time of the death of Eucratides I.

The choice of this site for the foundation of a city was probably guided by several factors. The region, irrigated by the Oxus, had a rich agricultural potential. Mineral resources were abundant in the back country towards the Hindu Kush, especially the famous so-called “rubies” (actually, spinel) from Badakshan, and gold. Its location, at the junction between Bactrian territory and nomad territories to the north, ultimately allowed access to commerce with the Chinese empire. Lastly, Ai-Khanoum was located at the very doorstep of Ancient India, allowing it interact directly with the Indian subcontinent.

Numerous artefacts and structures were found, pointing to a high Hellenistic culture, combined with Eastern influences. “It has all the hallmarks of a Hellenistic city, with a Greek theatre, gymnasium and some Greek houses with colonnaded courtyards” (Boardman). Overall, Aï-Khanoum was an extremely important Greek city (1.5 sq kilometer), characteristic of the Seleucid Empire and then the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom. It seems the city was destroyed, never to be rebuilt, about the time of the death of the Greco-Bactrian king Eucratides around 145 BC. Ai-Khanoum may have been the city in which Eucratides was besieged by Demetrius, before he successfully managed to escape to ultimately conquer India (Justin).

The mission unearthed various structures, some of them perfectly Hellenistic, some other integrating elements of Persian architecture:

– Two-miles long ramparts, circling the city

– A citadel with powerful towers (20 × 11 metres at the base, 10 meters in height) and ramparts, established on top of the 60 meters-high hill in the middle of the city

– A Classical theater, 84 meters in diameter with 35 rows of seats, that could sit 4,000-6,000 people, equipped with three loges for the rulers of the city. Its size was considerable by Classical standards, larger than the theater at Babylon, but slightly smaller than the theater at Epidaurus.

– A huge palace in Greco-Bactrian architecture, somehow reminiscent of formal Persian palatial architecture

– A gymnasium (100 × 100m), one of the largest of Antiquity; A dedication in Greek to Hermes and Herakles was found engraved on one of the pillars. The dedication was made by two men with Greek names (Triballos and Strato, son of Strato).

– Various temples, in and outside the city. The largest temple in the city apparently contained a monumental statue of a seated Zeus, but was built on the Zoroastrian model (massive, closed walls instead of the open column-circled structure of Greek temples).

– A mosaic representing the Macedonian sun, acanthus leaves and various animals (crabs, dolphins etc…)

– Numerous remains of Classical Corinthian columns

On a hunting trip in the 1960s, the Afghan Khan Gholam Serwar Nasher discovered ancient artefacts of Ai Khanom and invited Princeton archaeologist Daniel Schlumberger with his team to examine Ai-Khanoum. It was soon found to be the historical Alexandria on the Oxus, also possibly later named اروکرتیه Arukratiya or Eucratidia), one of the primary cities of the Greco-Bactrian kingdom. Some of those artefects were displayed in Europe and USA museums in 2004. The site was subsequently excavated through archaeological work by a French Archaeological Delegation in Afghanistan (DAFA) mission under Paul Bernard between 1964 and 1978, as well as Soviet scientists. The work had to be abandoned with the onset of the Soviet–Afghan War, during which the site was looted and used as a battleground, leaving very little of the original material. In 2013, the film-maker David Adams (photojournalist) produced a six-part documentary mini-series about the ancient city entitled Alexander’s Lost World.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ai-Khanoum

———————————————————————–

Δείτε το βίντεο:

Ай Ханум – Александрия Оксианская, Άι Χανούμ – Αλεξάνδρεια επί του Ώξου

https://ok.ru/video/1580031806061

Δείτε το βίντεο:

Ай Ханум – Александрия Оксианская, Ai Khanoum – Alexandria on the Oxus

https://orientalgreeks.livejournal.com/1738.html

Περισσότερα:

Александрия наша!

На каком основании узбекские власти отобрали древний город у Афганистана

АНДРЕЙ КУДРЯШОВ 29.08.19

Есть в Узбекистане античное городище Кампыртепа, расположенное в 30 километрах к западу от Термеза. 24 августа в рамках археолого-туристического форума «Узбекистан — перекресток цивилизаций» на территории этого городища состоялось торжественное открытие археологического памятника — Александрии Оксианской. Звучит сенсационно — особенно для тех, кто думал, что город-крепость Александрия Оксианская была построена в IV веке до нашей эры Александром Македонским во время его военных походов в Бактрию и находилась в Афганистане, в провинции Тахар.

Заместитель премьера Узбекистана Азиз Абдухакимов и хоким Сурхандарьинской области Тура Боболов перерезали символическую алую ленточку и объявили, что с этого дня именно археологический памятник Кампыртепа признан Александрией Оксианской и так он и будет теперь официально называться. Более того, на автомобильных трассах, ведущих к древнему городищу, уже установлены соответствующие указатели. Ученые, общественные деятели и журналисты, приглашенные на конференцию из сорока стран, в течение часа подробно осматривали живописные руины на берегу Амударьи, которую в античные времена называли Окс, — отсюда и Оксианская в названии здешней Александрии.

Научной основой для пиар-акции по открытию Александрии Оксианской на территории Узбекистана послужила недавно изданная в Ташкенте брошюра академика Академии наук Узбекистана Эдварда Васильевича Ртвеладзе. Брошюра эта носит сенсационное название «Кампыртепа — Александрия Оксианская: город-крепость на берегу Окса». В своей работе известный археолог оспаривает распространенное в научных кругах мнение, будто Александрия Оксианская располагалась в Афганистане, — там, где на левом берегу Пянджа находится городище Ай-Ханум.

Ай-Ханум был обнаружен французскими археологами Даниэлем Шлюмберже и Полем Бернаром в 1964 году. Случилось это, как говорят, по «подсказке» афганского короля Захир-Шаха. На территории Ай-Ханум нашли типичные греческие строения, которых не было на Кампыртепе: театр, агору и гимнасий.

Считается, однако, что реальное заселение этого греческого города не было связано с походами Александра Македонского. Оно началось лишь после распада его империи — в период правления диадоха Селевка I Никатора, который при жизни Александра Македонского был телохранителем великого полководца. Таким образом, расцвет поселения пришелся уже на эпоху Греко-Бактрийского царства (III-II века до нашей эры).

Древнегреческий историк Плутарх приписывал Александру Македонскому основание 70 городов — начиная от Малой Азии и Египта и вплоть до Индии. Современные историки, правда, полагают, что 60 из этих 70 городов существовали и до великого завоевателя, но были укреплены или перестроены его армией. Большинство же прочих Александрий достраивались и заселялись уже после смерти великого полководца.

Современная история Ай-Ханум сложилась достаточно печально. После сворачивания в 1978 году археологических работ городище разрушили местные жители. Они выкопали здесь множество ям — искали древние сокровища. Несмотря на это, Ай-Ханум до сих пор считается единственным крупным эллинистическим городом в Центральной Азии, городом, давшим эталонные памятники эллинистической культуры мирового уровня.

Городище Кампыртепа открыл Эдвард Ртвеладзе в 1972 году. Первоначально полагали, что археологи имеют дело с небольшой крепостью, охранявшей переправу через Амударью во времена Кушанского царства. Основные постройки Кампыртепы представляли собой цитадель, окруженную рвом, и «нижний город» с узкими улицами, который со стороны суши защищала крепостная стена с башнями. В ближайших окрестностях городища были также найдены керамические мастерские. Благодаря спонсорской поддержке конгресса США в начале 2000-х годов удалось восстановить часть внешней крепостной стены и одного кушанского квартала. Сделано это было с применением древних строительных методов. В частности, для формовки сырцового кирпича тут использовался лёсс, который брали у подножия крепостной стены. В своем нынешнем виде Кампыртепа включена в предварительный Список объектов всемирного наследия, охраняемых ЮНЕСКО.

Исследуя городище, академик Ртвеладзе провел аналогию между Кампыртепой и поселением Бурдагуй, которое упоминал персидский автор XV века Хафизи Абру.

«Бурдагуй — место на берегу Джейхуна (Амударьи), около Термеза. Говорят, оно существовало задолго до Термеза и было основано тоже Александром» — писал Хафизи Абру.

Раскопки ниже кушанского культурного слоя позволили выявить на Кампыртепе и эллинистический слой. Благодаря этому история городища удлинилась до IV века до нашей эры. В последние пять лет академик Ртвеладзе исследовал пойменную низину между Кампыртепой и нынешним руслом Амударьи — сейчас эта низина занята рисовыми полями. Здесь главный археолог Узбекистана сделал находки, которые он трактует как остатки типичной греческой гавани и маяка.

«Свое мнение о локализации Александрии Оксианской на месте Кампыртепа я высказал еще в начале 2000-х годов, хотя в то время археологических данных, подтверждающих этот тезис, имелось еще очень мало, — пишет академик Ртвеладзе в своей брошюре. — Сейчас их выявлено значительно больше. Это прежде всего размеры города-порта, в данное время протянувшегося вдоль Окса с запада на восток более чем на 400 метров, а также развитая градостроительная структура, состоящая из сильно укрепленного фуриона, — крепости с воротами, улицей, святилищем-храмом, некрополем и гаванью, включавшей порт с маяком, бухту для стоянки кораблей и пристань, где находились торговые пункты и ремесленные мастерские. Очевидно, в свете всех полученных данных, что Кампыртепа в конце IV — начале III вв. до н.э. представляла довольно значительное по площади поселение-город с весьма разнообразной структурой, которая ни на Ай-Ханум, ни в Старом Термезе для этого времени археологически не зафиксирована».

Есть, однако, скептики, которые возражают академику. Они замечают, что, хотя на Кампыртепе действительно есть археологические слои, которые можно отнести ко времени походов Александра Македонского в Бактрию, здесь нет убедительных свидетельств монументальной эллинистической архитектуры. По крайней мере, под более поздними культурными слоями они не выявлены. Особенно это касается гавани и маяка. Кампыртепа прекратила свое существование из-за значительного подъема уровня воды в Амударье. Гавань должно было смыть в первую очередь. Современное городище демонстрирует в его прибрежной части легко узнаваемый береговой обрыв. Как же смог ученый обнаружить признаки гавани на поверхности речного русла, вновь обнажившегося спустя два тысячелетия?

Тем не менее сторонники смелой гипотезы Ртвеладзе утверждают, что 77-летний академик имеет ответы на любые каверзные вопросы и открыт к научной полемике. Другой вопрос — нужна ли такая полемика властям Узбекистана? Ведь Кампыртепа, ставшая Александрией Оксианской, чрезвычайно перспективный туристический объект. В начале 2000-х годов в Сурхандарьинскую область, граничащую с воюющим Афганистаном, был запрещен въезд иностранным туристам, да и граждане страны были ограничены в посещениях этой территории. Сейчас же можно совершенно беспрепятственно посетить Термез и все находящиеся в его окрестностях достопримечательности — даже расположенные возле самой границы.

Более того, хоким Сурхандарьинской области Тура Боболов в комментарии «Фергане» сообщил, что власти соседствующих стран планируют организацию упрощенного трансграничного режима для туристов — чтобы человек или группа, интересующиеся артефактами истории древней Бактрии, смогли начать их осмотр в Узбекистане и продолжить в Афганистане.

https://fergana.agency/photos/110363/

Δείτε το βίντεο:

Ай Ханум – Александрия Оксианская, Ai Khanoum – Alexandria on the Oxus

https://vk.com/video434648441_456240369

Περισσότερα:

ВЫСТАВКА ПАМЯТНИКОВ ДРЕВНОСТИ И ПРОИЗВЕДЕНИЙ ИСКУССТВА АФГАНИСТАНА ПРОХОДИТ В СЕУЛЕ

Выставка памятников древности и произведений искусства Афганистана проходит в Национальном музее Сеула в Южной Корее.

«Изюминкой» выставки является знаменитое «золото Бактрии» из района Шибиргана.

Кроме того, посетители имеют возможность ознакомиться с произведениями греко-бактрийского искусства из городища Ай-Ханум, оно же «Александрия Оксианская» – города, расцвет которого пришелся на 1У в. до Р.Х. – 11 в. Р.Х., руины которого были обнаружены в 60-е годы ХХ в. французскими и советскими археологами в провинции Кундуз.

Городище являлось уникальным памятником эллинистической культуры в Центральной Азии.

Помимо собственно золота, в выставочной коллекции представлены серебряные украшения, различные изделия из стекла и керамики, а также скульптура и произведения мелкой пластики из известняка.

Как рассказал радио «Ашна» директор Национального музея Афганистана Фахим Рахими, показ коллекции произведений искусства и памятников древней культуры Афганистана в зарубежных музеях приносит стране пользу как с материальной, так и с духовно-нравственных точек зрения.

Указав на морально-нравственную ценность данной выставки, Рахими добавил, что ознакомление с памятниками древности позволит людям других стран ближе соприкоснуться с уникальной афганской культурой и древней историей.

По словам Рахими, первая выставка «золота Бактрии» и других древностей была организована в 2011 году в Париже. К настоящему моменту она уже объехала 11 стран мира, в частности Францию, Голландию, Германию, Норвегию, Великобританию, США и Канаду. Принято решение, что выставка будет проходить в различных музеях Южной Кореи до 27 ноября этого года.

http://afghanistantoday.ru/node/39841

Δείτε το βίντεο: Ай Ханум – Александрия Оксианская, Ai Khanoum – Alexandria on the Oxus, Αλεξάνδρεια επί του Ώξου

Περισσότερα:

Bactria, the territory of which Bactra was the capital, originally consisted of the plain between the Hindu Kush and the Āmū Daryā with its string of agricultural oases dependent on water taken from the rivers of Balḵ (Bactra), Tashkurgan, Kondūz, Sar-e Pol, and Šīrīn Tagāō. This region played a major role in Central Asian history. At certain times the political limits of Bactria stretched far beyond the geographic frame of the Bactrian plain.

Bactria in the Bronze and Iron Ages. The first mentions of Bactria occur in the list of Darius’s conquests and in a fragment of the work of Ctesias of Cnidos—texts written after the region’s incorporation in the Achaemenid empire. Ctesias, however, echoes earlier reports in his mention of campaigns by the Assyrian king Ninus and the latter’s wife Semiramis (late 9th and early 8th century B.C.). Thereafter, he states, Bactria was a wealthy kingdom possessing many towns and governed from Bactra, a city with lofty ramparts. A similar picture is presented in the Zoroastrian tradition (Avesta, Šāh-nāma), which speaks of the protection given to Zoroaster by a powerful ruler of Bactra (see ii, below).

While the existence of such a kingdom remains hypothetical, archeological investigations have produced evidence of big oasis communities grouped around a fortress (Dašlī). These communities, like those of the oases in Margiana, were already practicing a well-developed system of irrigation and carrying on trade in products such as bronze and lapis lazuli with India and Mesopotamia.

Bactria under the Achaemenids. After annexation to the Persian empire by Cyrus in the sixth century, Bactria together with Margiana formed the Twelfth Satrapy. Apparently the annexation was not achieved through conquest but resulted from a personal union of the crowns. Indicative of this are the facts that the satrap was always a near kinsman of the great king and that the Achaemenid administrative system was not introduced. The local nobles played a big part and held all real power. Their wealth is attested by the opulence of the Oxus treasure. Bactra occupied a commanding position on the royal road to India. Profits from the east-west trade as well as from the outstandingly prosperous local agriculture enabled the province to pay a substantial tribute (360 talents of silver per annum).

The Bactrians also made an important contribution to the Persian army. At Salamis they were under the great king’s direct command. At Gaugamela the Bactrian cavalry nearly turned the scales against the Macedonians. When Darius Codomannus, after his defeat in this battle, sought refuge in the Upper Satrapies, the Bactrian Bessos caused him to be murdered and then proclaimed himself king. Despite the resistance by scorched earth tactics conducted by Bessos, Bactria was conquered by the Macedonians and Bessos was delivered to them and put to death on Alexander’s order. Bactra then served as Alexander’s headquarters during his long campaign into Sogdia. After overcoming all the forces of resistance, Alexander took away 30,000 young Bactrians and Sogdians as hostages and incorporated a large number of Bactrians in his army. At the same time he settled many of his veterans in colonies planned to secure the Macedonian hold on Bactria.

Little information has been obtained from Achaemenid sites in Bactria. Bactra is deeply buried under the citadel (bālā-ḥeṣār) of present-day Balḵ. Drapsaca and Aornos, mentioned by the historians of Alexander, are usually identified with Kondūz and Tashkurgan, where excavations have yet to begin. More recently it has been suggested that Aornos may have been located at Altyn Delyār Tepe (Rtveladze, pp. 149-52), a site north of Balḵ where excavation was started but could not be pursued. Other sites from the Achaemenid period are Kyzyl Tepe and Talaškan Tepe on the Sorḵān Daryā, and Taḵt-e Qobād (the probable source of the Oxus treasure) on the right bank of the Oxus, the citadel of Delbarjīn, and the circular town of Āy Ḵānom II on the left bank. All show traces of fortifications built of dried mud or large bricks on massive platforms. At none of them has thorough exploration yet been possible.

http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/bactria

————————————————————–

Διαβάστε:

Aï Khanum

Āy Ḵānom or Aï Khanum (Tepe), a local Uzbek name (lit. Lady Moon hill) designating the site of an important Greek colonial city in northern Afghanistan excavated since 1965 by a French mission and which belonged to a powerful hellenistic state born of Alexander’s conquest in Central Asia (329-27 B.C.). Centered around Bactriana, the middle valley of the Oxus (Amu Darya), this colonized area was first part of the Seleucid empire, then, around 250 B.C., it became an independent kingdom which remained under Greek rule until approximately 150 B.C. when it was destroyed by nomad invasions from the northern steppes.

The city of Aï Khanum which controlled a fertile agricultural plain irrigated by an extensive system of canals (J.-Cl. Gardin and P. Gentelle, Bulletin de l’Ēcole française d’Extrême Orient, 1976, pp. 59-99) and a mountainous back-country (Badaḵšān) rich in minerals and semiprecious stones (rubies, lapis), was built at the junction of the Oxus river and of one of its left-bank affluents, the Kokča. Roughly triangular in shape (1,800 by 1,600 m), it encompassed within a girt of powerful mud-brick ramparts (P. Leriche, Fouilles d’Aï Khanoum IV: Les remparts d’Aï Khanoum, Paris, 1986) a lower town where most of the buildings were located and an acropolis on a hill (P. Bernard and D. Schlumberger, Bulletin de correspondance hellénique, 1965, pp. 595-657; P. Bernard, Proc. British Academy, 1967, p. 71-95).

Outside the ramparts lay a suburb and the necropolis. Although the Greek colonists kept their national language and way of life, the architecture of the town, combining mud-brick walls and stone columns and pillars, reveals a mixture of Greek and oriental traditions (P. Bernard, Comptes rendus de l’Académie des inscriptions et belles letters, 1966, pp. 127-33; 1967, pp. 306-24; 1968, pp. 263-79; 1969, pp. 313-55; 1970, pp. 301-49; 1971, pp. 387-452; 1972, pp. 605-32; 1974, pp. 280-308; 1975, pp. 167-97; 1976, pp. 287-322; idem, JA, 1976, pp. 245-75; P. Bernard et al., Fouilles d’Aï Khanoum I, pp. 1-120; Bulletin de l’Ēcole française d’Extrême Orient, 1976, pp. 6-51). Columnated porticoes of the Corinthian, Doric, and more rarely Ionic orders (P. Bernard, Syria, 1968, pp. 111-51) bespeak the hellenistic tradition as do the antefixes and tiles of the roofs and such typical buildings as a gymnasium, a theater, a fountain, and funerary monuments.

The gymnasium, of colossal proportions, consisted of several courtyards surrounded by rooms, of which the two principal ones were devoted to physical training and intellectual activities, and included extensive bath-facilities (S. Veuwe, Fouilles d’Aï Khanoum VI: Le gymnase, Paris, 1987). In the theater, made entirely of mud bricks and as large as the one in Babylon, the usual tiered rows of seats were interrupted by loggias for prominent people. In a fountain a water-spout carved to represent one of the characters of Greek comedy proves that the theatrical repertory itself was Greek. Funerary monuments for eminent citizens were built inside the ramparts and imitated Hellenic temples. In the most ancient of them—and the most modest—a certain Kineas was buried, who may have been the city’s founder.

In the precinct of this heroon a stele, on which was engraved a copy of the famous Delphic maxims which embody Greek wisdom, had been erected (L. Robert in Fouilles d’Aï Khanoum I, pp. 207-37). Alongside these buildings of Hellenic types there were others of Oriental tradition in which local elements were fused with Iranian and even Mesopotamian ones.

Three temples have been discovered, none of which has a Greek plan. One of them, a simple stepped podium in open air on the acropolis, is clearly related to Iranian and Central Asian sanctuaries of the Achaemenid period. Another, standing on a three-stepped platform, with a square plan and a broad vestibule leading to a smaller cella flanked by two sacristies, and whose walls are decorated with indented recesses, is also purely Oriental and can be compared with certain Parthian temples at Dura Europos. A third temple with a triple cella has the same wall-decoration and stepped platform. Although the official pantheon, as it appears on the coinage of the Greco-Bactrian kingdom, was, with a few exceptions, purely Greek (Cl. Petitot, RN, 1975, pp. 23-57; P. Bernard, ibid., pp. 58-69; 1973, pp. 238-89; 1974, pp. 6-41; Fouilles d’Aï Khanoum IV: Les monnaies hors trésors, Paris, 1985), this type of religious architecture implies a strong influx of local beliefs in the city-cults and suggests divinities of a syncretic nature.

The vast patrician mansions, with their front courtyard and the disposition of the secondary rooms grouped around the principal one which is usually surrounded by a peripheral corridor, except for the spacious bathrooms, have nothing to do with the traditional Greek houses (P. Bernard, JA, 1976, pp. 257-66). A huge arsenal housed the military equipment (F. Grenet, Bulletin de l’Ēcole française d’Extrême Orient, 1980, pp. 51-63). The city’s main building was a monumental palace—probably the governor’s—approximately 300 m2, which was situated in the middle of the lower town. It comprised several courtyards, two of them possessed columned porticoes, residential quarters, administrative sections with offices and reception rooms, and also a treasury in which was found a large number of storage jars, several of them bearing economic inscriptions in Greek (Cl. Rapin, Bulletin de correspondence hellénique, 1983, pp. 315-72), a large amount of fragments of cut and uncut semi-precious stones, among them a great quantity of lapis lazuli, and fragments of Greek literary papyri.

Although the columns and antefixes give a certain Greek aura, the compact aggregation of several ensembles in the same compound linked by a complex crisscrossing of corridors, the plan of certain units, the monumentality of proportions, and the repetitious symmetry, all point to Oriental conceptions. Similarly the pottery offers examples of Greek types as well as purely local forms (J.-Cl. Gardin in Fouilles d’Aï Khanoum I, pp. 121-88).

In the field of fine arts, the Greek colonists were much more conservative and seemed to have been satisfied with traditional Greek productions, as can be seen from fragments of stone statuettes, from the water-spouts of a fountain representing respectively a dolphin-head, a dog-head and a comic mask, and from the pebble-mosaics which paved the bath-rooms of the palace and were decorated with floral and animal designs (P. Bernard, Bulletin de l’Ēcole française d’Extrême Orient, 1976, pp. 6-24).

A beautiful medallion in gilt silver, figuring the goddess Cybele on her lion-driven chariot, followed by one of her priests holding an umbrella over her and facing another one who sacrifices at an altar, represents, through its flat Hieratic style, a rare exception to this general trend (P. Bernard, Comptes rendus de l’Académie des inscriptions et belles lettres, 1970, pp. 339-47).

Fragments of life-size statues modeled in clay or stucco attest the introduction of a technique which was subsequently spread all over Central Asia. As one might expect in such a wealthy and urbanized society, workshops were active in producing all kinds of artifacts both for utilitarian purposes, for example grindstones of a specifically Greek type, and for the luxury market such as carved ivories (P. Bernard, Syria, 1970, pp. 327-43) and vessels of dark schist inlaid with colored stones (H.-P. Francfort, Arts Asiatiques, 1976, pp. 91-95).

Τις βιβλιογραφικές παραπομπές θα βρείτε εδώ:

http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/ay-kanom-or-a-khanum-tepe-a-local-uzbek-name-lit

——————————————————————-

Hellenistic Bactria The future of the Greek colonization of Bactria hung in the balance when the colonists rebelled in 326, after learning of Alexander’s death, and again in 323; but they were reduced to obedience, and Bactria was then combined with Sogdia to form a satrapy under Philippos. After the establishment of the Seleucid regime, Bactra became for a time the headquarters of Seleucos I’s son Antiochos, who was deputed to defend the eastern satrapies against the growing might of the Mauryan empire. The weakening of Seleucid power particularly in the reign of Antiochos II (261-247) enabled first Parthia, then Bactria to secede. The independent kingdom of Bactria was founded by Diodotos. On coins minted at Bactra the figure of Antiochos is replaced with that of Diodotos over the royal title (the figure on the reverse being Zeus brandishing a thunderbolt).

In 208 Antiochos III set out to reestablish Seleucid authority and marched into Bactria. After fending off a move by the Bactrian cavalry to halt his advance, he blockaded their king Euthydemos in the city of Bactra. The siege dragged on for two years, and in the end Antiochos had to recognize Bactria’s independence and sign a treaty of alliance with Euthydemos.

The Greco-Bactrian kingdom was bounded in the south by the Paropamisadai (Hindu Kush) and in the east by the mountains of Badaḵšān. In the west it was in direct touch with the Parthians, who recovered Parthyene after the departure of Antiochos III and seized the Marv oasis. Scholars now generally accept the view that its northern frontier lay on the line of the Ḥeṣār mountains (between the Oxus and Zarafšān valleys; Bernard and Francfort, pp. 4-16) rather than the view, based on the rarity of finds of Greek coins north of the Oxus, that it lay on that river (Zeĭmal’, pp. 279-90). These frontiers shifted in the course of the kingdom’s career. In the north, Sogdia was annexed at an uncertain date. In the south, a campaign of conquest launched by Demetrios I about 190 led to the creation of a Greco-Indian kingdom with its center at Taxila, but relations did not remain close for long. The Greco-Indian kingdom survived for half a century after the collapse of the Greco-Bactrian kingdom.

The Hellenistic period appears to have been a prosperous time for Bactria. One indication of this is the high quality of its coin issues. Strabo echoes memories of the period when he speaks of “Bactria of the thousand towns.” Until recently, however, archeological investigations, mainly at Balḵ (Bactra) and Termeḏ, were so fruitless that A. Foucher could speak of the “Bactrian mirage.” The situation has been radically changed since 1964, when the remains of a large city were discovered at Āy Ḵānom. Excavations, vigorously pursued until 1978, have shown that this city at the confluence of the Oxus and the Kūkča river was the capital of eastern Bactria. Strongly fortified and dominated by an acropolis and citadel, it was built on a regular plan well suited to the site and had a number of fine edifices typical of a Hellenistic city: a heroon (monument to the founder), gymnasium, theater, fountain with sculptures, and peristyle courts. On the other hand, the huge palace occupying the central position and the upper class dwellings are clearly influenced by Iranian concepts, while the temples and the fortifications show signs of Mesopotamian inspiration.

The abundant and datable material from Āy Ḵānom provided guidance for other site investigations, which were pursued with vigor on both sides of the Oxus. These have revealed the great scale of the irrigation projects undertaken to complete the already substantial works of the preceding periods. Furthermore several new sites of towns or fortified settlements were identified and provisionally excavated, though Termeḏ (probably a foundation of Demetrios) remained inaccessible. In general these are sites of towns founded in the later years of the kingdom’s existence; they are smaller than those of the cities founded by the Seleucids and have a markedly military character, with a citadel overlooking a geometrically planned settlement surrounded by ramparts. Noteworthy are the quadrangular town of Delbarjīn in the north of the Balḵ oasis, and the fortresses of Kay Qobād Šāh, Ḵayrābād Tepe, Qaḷʿa-ye Kāfernegān, and Qarabāḡ Tepe on right bank tributaries of the Oxus. Somewhat later came the discovery of the site on the right bank of the Oxus called Taḵt-e Sangīn, which is surrounded by stone fortifications (most unusual in this region); excavations there have uncovered a sanctuary of the Oxus god and yielded abundant materials closely resembling those found at Āy Ḵānom (Litvinskij and Pitchikian, pp. 195-216).

The last period of the Greco-Bactrian kingdom is marked by the reign of Eucratides, who overthrew Demetrios and thereby started a long conflict with the descendants of Euthydemos who remained in power in India, which continued under his successors. The protracted hostilities probably explain, in part, why the kingdom lost strength and succumbed to a nomad invasion, which ended Greek rule in the region. It is known that Āy Ḵānom was abandoned by the Greeks and pillaged by neighboring populations in 147. According to the Chinese traveler Chang Chien, Ta Hsia (Bactria) in 130 consisted of a multitude of petty principalities, lacking a supreme chief but all under the domination of the Yüe Chih tribes whose camping grounds lay on the right bank of the Oxus.

Τις βιβλιογραφικές παραπομπές θα βρείτε εδώ:

http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/bactria

——————————————————————-

Γενικά:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ai-Khanoum

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Greco-Bactrian_Kingdom

https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ай-Ханум

https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/Греко-Бактрийское_царство

————————————————————–

Κατεβάστε το κείμενο σε Word doc: